Jim’s first Lessons from the Past post prompted quite a few of us to think about the lessons from our primary schooling. My memories and feelings about my own schooling are mellow and warm – a state not shared by everyone who responded.

One friend, for example, commented that Catholic schools of the fifties and sixties were less sexist in their corporal punishment. She, aged five, was caned on her first day at school for following a group of boys into the boys’ toilet. Suffer the little children.

Botany Public School didn’t separate boys and girls in lesson time. In fact, for a lot of the time I shared a desk with a boy, someone called Kevin in Grade 1, William Dang in Grade 2 and Peter Isaacs in Grades 5 and 6. Mostly boys and girls sat in single-sex pairs at double desks but if there were odd numbers some conscientious boy and girl would get to share a desk, in the front row under the teacher’s eye. That was me.

Being tagged as conscientious and reliable earned me, like Jim, the privilege of walking out of the school, across the main road and down to the corner shop in Grades 5 and 6 to buy my teacher’s cigarettes for him. I was also on the roster to put the 78rpm record on the gramophone player in the Headmaster’s office at the beginning of the day, after recess and after lunchtime, so we could all march into class. When rostered, you got to choose the record as well as lowering the arm onto the vinyl without a ‘crunch’. I always chose ‘Colonel Bogey’ or ‘Sussex-by-the-Sea’.

There were a range of other jobs, all, in my memory, regarded as privileges. Maybe these were our ‘authentic’ learning experiences. A couple of reliable boys (Peter Isaacs was one of them) got to mix up the ink each week and fill up the inkwells in the centre of each double desk. A messy job, leaving stained hands – no protective gloves provided. The same boys also got to mix the paint and put out the paper for our Wednesday afternoon painting lesson – delivered via the loudspeaker at the front of the room from somewhere – I assume – in Bridge St, Sydney. I remember painting patterns in time to music. We had singing lessons the same way (led by ‘Uncle Terry and the Fort St Boys Choir”), and folk dancing outside on the asphalt, with the loudspeaker blaring across the playground.

The most important jobs of the day however, were those involved in ensuring the efficient and effective distribution of milk at morning recess. On the recess bell we were all marched (no music this time) to our allotted class space on the asphalt, two lines per class. At the top of the job hierarchy were the milk monitors – two boys from each class who collected the wooden crate of milk and, one on each side, carried it between the class lines. We each took a bottle (1/3 pint) as the crate went past. Behind the milk boys came the straw monitor – a girl holding a glass jar full of straws. Then there was the girl in charge of the bin for the bottle tops and straws. The milk boys’ job wasn’t finished until the empty bottles were back in the crate. Then we got to play. I have no doubt that milk was important in improving public health in post-WWII Sydney. It was delivered to schools every morning and left in what shade was available in the Sydney summers. Having a job was your best chance of avoiding drinking the milk, but even then, you had to be lucky. Teachers were very conscientious about ensuring we drank the milk.

I was occasionally a straw monitor. My friend Vivienne remembers being in charge of the bottle-top bin. She thinks I was also in charge of ‘the library’ – a few books kept in the downstairs corridor. I do remember spending time covering the books in the thick, slate grey paper that signified ‘library book’. The best bit was using white ink to write the title on the grey cover. Both Vivienne and I think we were the only borrowers. Just as well really, as there were not enough books for even one whole class to borrow. When in my second year of University on a Teachers’ College Scholarship, I did my required 2 weeks ‘practice teaching’ back at my primary school, the new Principal was engaged in a battle with the NSW Education Department to get a library for the school. His argument, which impressed me greatly, was that for the kids at the school, a library in two or three years time was too late. Vivienne and I read everything, borrowing each other’s Christmas and birthday books, Sunday School prizes and anything behind the slate grey paper. The other 42 kids in our class however, might have been enticed into sharing our passion, by a range of appealing books.

My other memories are of routine. In Grades 5 and 6, after the marching came 20 mental arithmetic questions delivered orally, followed by 10 maths ‘problems’ from the board. Then it was some form of grammar. Clauses are strong in my memory – noun clauses, adverbial clauses of time, place, cause and condition. At 12 noon we took a weather reading. I say ‘we’. Again, there were jobs for a few. I measured the shadow cast by a 12 inch ruler nailed to a wooden block. Two boys observed the clouds. A wind monitor measured wind direction and a temperature monitor read a mercury thermometer. These were all charted, by the teacher on various boards around the room. What did I learn from this? That the shadow at noon taken in the same place got progressively longer and shorter throughout the year and that clouds had fantastic names like nimbus, cumulus, stratus and combinations of those; and that I was trusted.

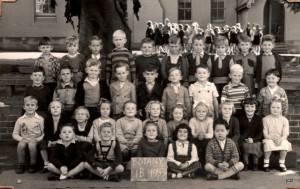

In 1957, when I was in Grade 5, the school introduced a uniform – navy blue tunic and white blouse for girls, navy drill shorts and white shirt for boys, pretty standard for primary schools of the day. My parents were unimpressed. My clothes were all home-made and there was no budget for tunics. My mother planned to find a part-time job the following year in order to pay for a uniform when I went to high school. My father, a union delegate, knew that ‘free, compulsory and secular’ did not mean compulsory uniform. In vain did the headmaster call me to his office, explain the new uniform policy and argue that I would need a navy blue tunic anyway in a eighteen month’s time, to go to either Gardeners Rd Domestic Science School, or Crown St Commercial High School, the assumed destinations for Botany kids. My parents, I solemnly told him, expected me to go to the selective high school and wear a brown tunic. Navy blue wasn’t in our world. I was polite but firm – my heart in my mouth but my resolve steady. The headmaster was a gentleman, and let me go back to class. My proud parents told the story over and over again. “No,” my mother would say, “she doesn’t mind. She’s above that.” They proudly displayed the class photo, and worse, the choir photo, which some girls thought I ruined.

Did I care? Of course I cared. Did it build resilience? I dare say. However, when, some fifteen years later, the job market meant I settled and had my own children 2000km away from my parents, I confess the relief was significant. Distance relieved the pressure in the way nothing else had.

Apart from the uniform issue, I cannot recall being in trouble or punished at primary school. My hand writing was the cause of some concern, but didn’t generate punishment. I have two memories, though, of getting into trouble with my parents over things that happened at school. Both relate back to the story of my friend’s experience at the beginning of this blog post. At some time during my first year at school I asked why the boys had a separate toilet. What did it look like, I wondered. How could there be any difference? One of the boys, Harry Morris, offered to show me through the boys’ toilet block. He gave me a guided tour – no demonstrations, just a tour, after checking it was not in use. Either no teacher noticed, or none of them cared. My parents, however, did. I was, they said, never, ever, ever to do that again. I got the message.

There was, however, worse to come in Grade 2. Each week a variety of clergy or religious laity arrived at the school to take ‘Scripture’ classes. I was Church of England and a regular Sunday School and Church attender. However, we C of Es were often without a Scripture teacher. On those occasions a teacher would read to us from the NSW Education Department book of Scripture stories. We’d been through it many times. Miss Lonegan, however, never failed to turn up to teach the Catholic kids, telling them stories of saints and giving them, every week, little holy pictures to take home. The ever obliging Harry Morris offered to take me to Catholic Scripture. I had a great time. When I told my parents, however, about my smart move, and showed them my holy picture, I unleashed anger and recrimination far greater than when I visited the boys’ toilet. I had put my soul in danger. I had crossed a line no decent child crossed. Miss Lonegan might have a lovely lilting name, she might look like a kindly, plump lady, but she was out to capture me, mind and soul. No teacher ever made me feel so small.

I had a happy childhood. My home and my school were both loving and caring, ambitious and respectful of intelligence. My parents and teachers did their best for me. When a conflict arose, however, school had no chance.

Corporal punishment damaged more than the boys on whom it was inflicted. The brutality and humiliation damaged all of us who witnessed it. In spite of that, my primary schooling served me well. It introduced me to adults who earned a living using their brains, it gave me things to do and think about and it taught me how to be around kids with different aspirations. It also gave me Vivienne’s friendship – the experience of finding a kindred spirit – still strong more than 50 years later.

She’s not a Catholic, but I have plenty of other friends who are; all power to Miss Lonegan and some great teachers!

One Response to My good old days